On Patricia Springborg: “Reading Hobbes Backwards” (1)

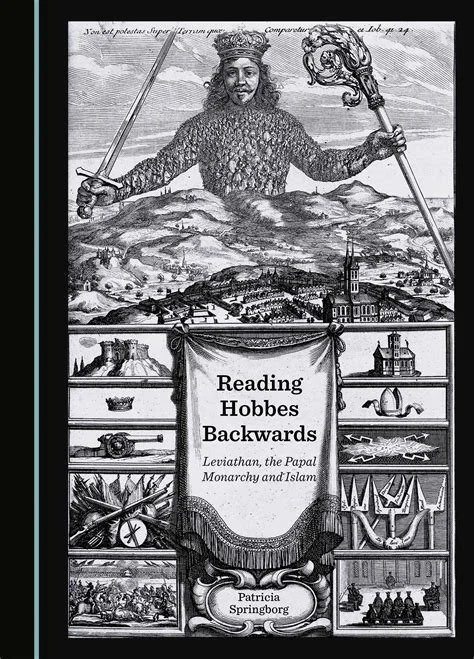

This online colloquium is dedicated to discussing Patricia Springborg's book, Reading Hobbes Backwards: Leviathan, the Papal Monarchy, and Islam, published by Cambridge Scholars Publishers in October 2024. The discussion will commence with an introduction by Patricia Springborg followed by three critical commentaries, presented by Delphine Thivet, Jeffrey Collins, and Elad Carmel. Subsequently, the Professor Springborg will respond to her critics. We extend our gratitude to Cambridge Scholars Publishing for their support of this colloquium.

Patricia Springborg is Honorary Professor in the Department of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney, Australia.

I. Introduction: ‘Reading Hobbes Backwards, and Leviathan: Hobbes the Peace Theorist’, by Patricia Springborg

If the 20th century could be summarized as having seen the rise and defeat of fascism in WWI and WWII, followed by the Cold War and its settlement; the 21st century has already seen two very different climacteric events: the 9/11 attack by al-Qaeda on the US Trade Centre in New York in 2001; and Brexit, the withdrawal of the UK from the European Union on January 31, 2020, after a 27 year membership dating from January 1, 1973. Such significant moments in the cycle of Empires, may also justly be referred to as ‘Pocockian Moments’, after the accounts by the great 20th and 21st century historian J. G. A. Pocock, who writes about empire as a ‘colonial’, like me; and was indeed the supervisor of my MA thesis, my life-long inspiration and friend. The work of Pocock, along with Quentin Skinner, Peter Laslett, and John Dunn, one of the founders of the Cambridge School of Contextual Historians, is distinctive precisely because he wrote from the perspective of a ‘colonial’. For, the context in which he situates Hobbes is not only that of the ‘political languages’ in which British 17th century constitutional debates were conducted domestically. Pocock distinctively addressed Hobbes’s work in the context of the rise of early modern maritime empires on the back of colonization of the Americas; which was read by contemporaries through the lens of the rise of Rome. If the ‘political languages’ approach to contextualism is an antidote to the longstanding tendency to read the political theory ‘classics’ as a discourse conducted in ‘great books’ in which philosophers addressed one another down the ages over the heads of participants in events; the approach of those concerned with the cycle of empires involves a different vulnerability – and that is contamination by concerns of the immediate present – hence the reading of empire in terms of the rise and defeat of fascism in WWI and WWII, followed by the Cold War and its settlement; and ongoing concerns under the Trump presidency, which might suggest another turning point in the cycle of empires. Pocock himself was only too well aware of this vulnerability, as his monumental study of Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire demonstrates, entitled by Pocock, significantly, Barbarism and Religion (6 vols. 1999-2015). For, Hobbes was a peace-theorist, and it is as a peace-theorist that my book, Reading Hobbes Backwards: Leviathan, the Papal Monarchy and Islam (2024), treats him.

It is sometimes forgotten that Hobbes’s greatest political works were written in exile at the Paris court of Henrietta Maria, the Catholic Queen of Great Britain, along with the King-in-waiting, her son Charles II, to whom Hobbes was mathematics tutor, and for whom Leviathan (1651), as an ‘advice book’, was written. In Paris Hobbes was engaged in formulating the tripartite philosophical system on which he staked his career, comprising De Corpore, ‘On body’, De Homine, ‘On Man’ and De Cive ‘On the Citizen’. Intended both for the benefit of the British court in exile and French members of the Cavendish circle including the famous philosopher Marin Mersenne, he acknowledges that impending civil war in Britain ‘plucked from me’ the third part, De Cive, out of sequence. De Cive (1642, 1647), I argue, stands midway between Hobbes’s earlier commissioned scribal publication, The Elements of Law Natural and Political (1640), circulated in MS by his patron William Cavendish, the Marquis of Newcastle, to persuade the Short Parliament to vote Charles I ‘Ship Money’, or funds to conduct its war with Spain; and Leviathan, which was not commissioned at all, and Hobbes’s first work in his own voice. Leviathan, a work of great courage, in which Hobbes undertakes to speak truth to power, as I shall argue, differs in form and content from his earlier commissioned works. It may or may not have been first written in Latin. But De Cive was certainly written in Latin, the language of European literacy, for which Hobbes was also hired as a tutor, writing some of his most important works in both Latin and Greek, the languages of civic humanism, which established his credentials to compete in the patronage systems which governed Stuart Britain as they were later to govern Hanoverian Britain – and to some extent still govern it today.

In Reading Hobbes Backwards: Leviathan, the Papal Monarchy and Islam (2024), I revisit the work of Thomas Hobbes, whose peace theory in Leviathan, belongs to the first, and perhaps the most significant body of encyclopaedic philosophy in the English language, intended, he says in his Latin verse Vita, to ‘last to all eternity’. And yet Leviathan, almost 350 years after the death of its author, is still an essentially contested text; this, I believe, because the change to the cycle of empires it represents is also still essentially contested. In my book I try to show that the tendency to read Hobbes back from the present, otherwise known as historicism, obscures the very assumptions that preoccupied him, as a product of his age. For the 17th century saw not only catastrophic religion-based European civil wars which were a consequence of the Protestant Reformation and schisms among Christians that had been growing for millennia. But it also saw the break-up of united Western Christendom, which had survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE; the schism between the Eastern and Western Roman Empires of 1054 CE, formalized by the institutional separation of the Roman Catholic Church in the Western Empire, and the Eastern Orthodox Church in the East; and the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1475.

The society of independent sovereign states, as it was constituted in 17th century Europe, saw not only the rise of new empires based on colonialism and emergent capitalism, but it also saw a scientific revolution, based on the work of the post-Galilean novatores, or innovators, science that was importantly engaged in state-building. Under way since the late Middle Ages, this scientific revolution, depended in turn on the transmission of mathematics and geometry, from the ancient Greek, Egyptian and Babylonian empires in the pre-Christian past; sciences curated, along with the Aristotle commentary tradition by Jewish, Islamic, and Christian civilizations which inherited their space. These sciences were then transmitted back to a Europe, more or less barbarized by 1000 CE, as a consequence of the break-up of the Roman Empire and the invasion of Gothic tribes. Points of entry for the great volume of Arabic and Persian MSs transmitted from the 13th century, were the Universities of Paris and Oxford, which also curated them, perpetuating the Aristotle commentary tradition.

Thomas Hobbes, an Oxford student educated in the Aristotle commentary tradition and a practitioner of the ‘new science’, had been engaged by his Cavendish patrons for his philosophical talents; a clientage network, positioning itself to profit from the new mercantile imperialism. In a series of commissioned texts, some scribal and some printed, Hobbes had explicated the new science on which this philosophy was based – claiming intellectual property in his work almost obsessively, in correspondence, letters dedicatory, and other high-profile vehicles like his posthumously published verse Vita, available in Latin and English. For, as a baronial secretary he had also been employed by his patron, William Cavendish the 2nd Earl of Devonshire, to deputize for him as an administrator in the Virginia and Bermuda Companies, imperilled in the parliament, following the Indian massacre at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1622. Leviathan, a demonstrably non-commissioned work, written by Hobbes, speaking in his own voice, was a summation of his experience in the Virginia and Bermuda Companies, as well aa a succinct analysis of the patronage system in which he was employed and its vulnerabilities.

Leviathan, a non-commissioned work, was nevertheless an important advice-book by his old pupil for the new King, an assumption on which Noel Malcolm’s authoritative edition of Hobbes’s Leviathan (OUP, 2012, 3 vols) is predicated. Prompted by Malcolm’s breathtaking claim in his early essay, ‘Hobbes, Sandys, and the Virginia Company’ (1981/2002) that: ‘The problem of the American Indian in Hobbes’s works ... is akin to the problem of the dog that did not bark in the night’ (Malcolm 2002, ‘Hobbes, Sandys and the Virginia Company’: 75), my current work on, Hobbes’s Leviathan at a turning-point in the cycle of empires, is dedicated to the memory of my old professor J. G. A. Pocock, who sadly died in December 2024, just a few weeks short of his 100th birthday. It responds to a number of recently published works serving to deny Malcolm’s extraordinary conclusion, that the ‘four references to American Indians, the brief discussion of colonies in chapter 24 of Leviathan, and the single mention of the early administration of Virginia exhaust the direct echoes, in Hobbes’s works, of his involvement in the Virginia Company’ (Malcolm 2002: 76). A position that he nevertheless seems to hold to this day. My current work addresses the ‘moment’ at which the constitutional logic of the state, as a ‘body politic’ created by incorporation – with consequences for representation and governance – coincided with that of the great chartered trading companies responsible for the colonization of the Americas. It is anticipated already in Reading Hobbes Backwards, which is the 7th in a series of books I have written exploring aspects of ‘the cycle of empires’, to which I am now considering a sequel: ‘Hobbes’s Leviathan at a Turning Point in the Cycle of Empires’.