On Patricia Springborg: “Reading Hobbes Backwards” (3)

Patricia Springborg’s Reading Hobbes Backwards often reads like a reflection on decades of Hobbes scholarship, with its multiple themes, developments, and controversies. In this, her own voice and contribution play a decisive role. I would therefore like to begin this brief comment with a personal reflection on how Springborg’s work has influenced my own research from the very start.

In 2010, I embarked as a Master’s student on what would become my longest project to date: exploring the complex relationship between Thomas Hobbes and English deism. I started by wondering if Hobbes could be seen as a deist or perhaps a proto-deist of some kind. Over the years, I ended up focusing more on Hobbes’s rich and unique reception among deists and freethinkers, becoming increasingly convinced that it was rather the deists who proved to be Hobbesian in some particularly distinctive ways. This argument ultimately became the basis for my book, Anticlerical Legacies (Manchester University Press 2024).

Back then, Patricia had just written a paper titled ‘Hobbes the Atheist and His Deist Reception’ (which would appear in M. Geuna and G. Gori, I filosofi e la società senza religione, il Mulino, 2011). I emailed her asking for a copy and, to my surprise, she got back to me quickly and kindly, sent me the paper, and kept the conversation going over email: ‘let me know what you decide about Hobbes’s deism’, she wrote at one point. Later, when I consulted her on Hobbes’s religious—and irreligious—commitments, she responded: ‘in brief, what I think is that Hobbes talks out of both sides of his mouth at once!’ (as many would agree; and I hope she would not mind me sharing this here).

Indeed, one of Springborg’s most significant contributions to Hobbes scholarship is her consistent emphasis on the central role of religion in his project—most notably through her recovery of his long-neglected Latin poem Historia Ecclesiastica (first published in 1688, translated into English in 1722, and edited by Springborg in 2008), in which Hobbes’s anticlericalism, attack on priestcraft, and arguably proto-deistic tendencies are evident. This point was central to her 2011 paper and it reappears in Reading Hobbes Backwards, where she observes that in the poem, ‘Hobbes’s account morphs from being a classic slander of the sophists to being a deist tirade against the clergy’ (379), rightly highlighting the intimate link between anticlericalism and deism. Elsewhere in the book, she states that the poem shows Hobbes’s lifelong role ‘as an anti-sectarian who embraced both local and continental traditions of anti-clericalism’ as well as ‘a forerunner of a long tradition of anti-Trinitarianism, anti-clericalism, scepticism, and Socinianism’ (xviii, xxiv). This is a fair assessment, as the radical and subversive strands of Hobbes’s reception in England—and beyond—clearly demonstrate. What is more, Hobbes’s anticlericalism is arguably one of the most crucial keys to understanding his political thought as a whole. Historia Ecclesiastica, which, according to John Aubrey, was meant precisely to expose ‘the encroachment of the clergie (both Roman and reformed) on the civil power’ (xxviii), is therefore an especially crucial resource—and thus, the appendix, where Springborg provides a detailed discussion of this work, is as a particularly valuable part of her book.

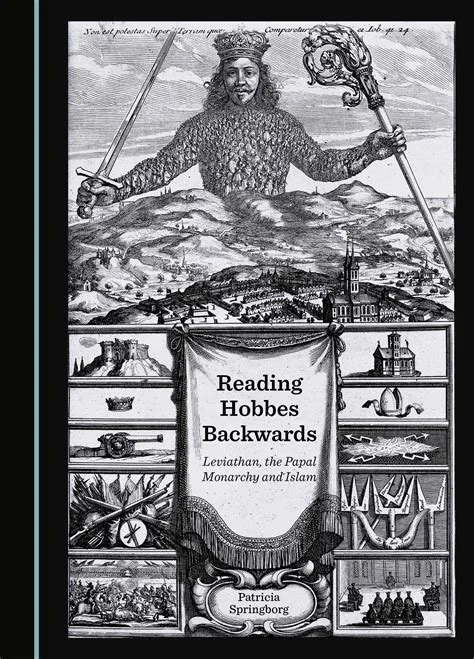

The theme of Hobbes’s anticlericalism appears throughout Reading Hobbes Backwards. Chapter 5, for example, explores the broader implications of Hobbes’s attempt to write a history of the papal monarchy—a critical one, to be sure—portraying ‘the papacy as a corporate entity with imperial ambitions and institutional strategies to achieve them’ (283). This tendency is found in Historia Ecclesiastica, which states in a distinctively Hobbesian manner that ‘popes by their own cunning overcame all the monsters that the earth produces’ (288). This effort, Springborg argues, sheds light on Hobbes’s overall oeuvre, including Leviathan, most clearly but not only in the last book, ‘Of the Kingdom of Darkness’. Even Leviathan’s frontispiece, she suggests, ‘constitutes a striking representation of the papal monarchy at its height … whereby members of the Christian community are incorporated in its head, the pope, to constitute the … mystical body of Christ’ (266). Perhaps, Springborg hypothesises, the word ‘Leviathan’ itself—and its association with the infamous beast from the Book of Job—was a late addition, a kind of ‘decoy’ even, intended to obscure the medieval and scholastic connotations typically associated with such Christian notions.

It is at this point that Springborg’s approach—reading Hobbes backward—seems to come into play, although it would have been helpful to elaborate further on the nature and scope of this proposed methodology, particularly beyond specific examples. Ultimately, this is a thought-provoking chapter, rich in both textual and contextual investigations, connecting different aspects of Hobbes’s thought. Beyond the justified renewed attention to the visual aspects of Hobbes’s works, the main claim regarding Hobbes’s use of the history—and representation—of papal power seems to leave several questions open. For instance, in what sense exactly was Hobbes ‘indebted’ to this specific kind of Christian imagery? If he strategically reappropriated it, presumably only to turn it on its head, why would he then feel the need to deflect his readers’ attention from it? And if this was indeed the case, what can Hobbes’s account of the papacy—rightly seen as ‘a subject in its own right’ (263)—reveal that goes beyond his well-known anticlericalism and that has otherwise been overlooked regarding his political, religious, and philosophical views? As Springborg once again successfully shows, Hobbes’s greatness promises to fuel many more topics—and years—of new and original studies.

Elad Carmel

University of Jyväskylä