Reading Hobbes Backwards (1)

This online colloquium is dedicated to discussing Patricia Springborg's book, entitled Reading Leviathan Backwards. The discussion will commence with three critical commentaries, presented by Jeffrey Collins, Elad Carmel, and Delphine Thivet. Subsequently, the author will respond to her critics. We extend our gratitude to Cambridge Scholars Publishing for their support of this colloquium.

It is my pleasure to offer this comment on Patricia Springborg’s new book, Reading Leviathan Backward. Dr. Springborg’s Hobbes scholarship, with its particular focus on ecclesiology and religious conflict, has long made an important contribution to the field. She is known, I think it fair to say, for a fearless originality. The chapter I have been asked to comment on – Chapter Six, “Hobbes on the Holy Roman Empire and Bodin” – is a case in point. It brings together two understudied subjects that bear some relation, one to the other, and promise unique angles of vision on some Hobbesian problems.

The chapter makes a number of claims, some of which are more speculative than others. That Hobbes wrote Leviathan with an eye on civil turmoil in both the British and European contexts is quite likely. As he repeatedly asserted, the basic cause of “all” the civil wars in Christendom was the division of temporal from spiritual authority, and he was of course very well aware that England was not the only Kingdom to have suffered from such wars in his own lifetime. That said, the claim that Leviathan was “simultaneously” addressing English and European audiences does run into the obvious problem that the text was composed in English, a language very little read on the continent. Hobbes presumably intended a Latin translation earlier than the actual one that he executed in the 1660s, but how immediately is very unclear. Untranslated, the work was essentially inaccessible to Europeans.

But this is perhaps a minor point. The broader problems of “Christendom” were surely on Hobbes’s mind when he composed his masterwork, and that broader context would have been relevant even to his English reading audience. To be sure, Hobbes proves reticent in commenting on the religious wars that must have immediately confronted his attention in the 17th century. His broad account of seditious clerical usurpation and dangerous “dualist” accounts of sovereignty focuses primarily on the Middle Ages. There are very few bright spots in that story (in Leviathan or in his later Restoration works of sacred history). The medieval Holy Roman Emperors, like their royal counterparts in medieval England, mostly function as victims of the papal monarchy at its height. The humiliation of Frederick Barbarossa, repeatedly recounted by Hobbes in various texts, is a case in point.

The possibility that 17th century European politics as it related to ecclesiology influenced Thomas Hobbes has mostly focused, in existing scholarship, on the French context. (One thinks of the scholarship of Stefania Tutino and Amy Chandran, among others.) As Dr. Springborg notes, there has been considerable work on Hobbes’s associations among that faction of the English Catholic Chapter (headed up by the priest Thomas White) most influenced by Erastian, Gallican Catholicism. Hobbes’s own civil science, in turn, helped to shape the loyalist and anti-papal direction of that faction’s political writing in the 1650s and later decades. The French wars of religion, and the resistance theory that these produced, loom behind this connection. And of course Hobbes spent a great deal of time in France during the crisis (English, French, and German) of the mid-century. We have some evidence of his admiration for the French Monarchy, and his own qualified tolerationism – which construed religious freedom as a prudent “indulgence” granted by sovereignty – was modeled on the politique strategies of the Bourbon dynasty. France, in other words, was a country where the problem of religious civil war and clerical usurpation had seemingly produced a new science of absolute sovereignty (Bodin’s, in fact) that paralleled and anticipated – and then amplified – Hobbes’s own.

The Holy Roman Empire is a far less clear-cut case. To be sure, eventually, Imperial legal and constitutional theorists would be drawn to Hobbes’s own system as they confronted the complex question of sovereignty within the multiple Kingdom that the Empire represented. Pufendorf is the clearest case. It is less clear, however, why Hobbes’s would have viewed the Empire as any sort of model, or even to have had “ambivalent” feelings about it (327). The Empire was in many respects a catastrophic stew of various forms of “divided sovereignty”. Its federated composition, elected head, prince bishops, and religious divisions make it more plausible as a foil for Hobbes. It is surely interesting that he does not write much that deployed the Empire in this manner, as a negative case. But that alone does not indicate that he saw much to admire there.

Dr. Springborg is aware of this, but attempts to nuance Hobbes’s possible interest in the Empire in two ways: first, by claiming that the Empire might have functioned as an example of a pacified multi-confessional state for Hobbes. She writes “over almost a millennium it had achieved peace between the confessions, Christians, Moslems and Jews. (327)” This is a somewhat strained point, given the religious strife that bedeviled the Empire throughout the Reformation era and during the crisis of the mid-17th century that served as the occasion of Hobbes’s own political theory. Hobbes cannot have viewed the territorialized religious pluralism of the Empire, which was arbitrated by the prerogative of subordinate powers within the Empire, as anything other than a fatal compromising of the Emperor’s singular power. The Emperor did not dispense indulgence on his own authority in the manner of the Bourbon kings.

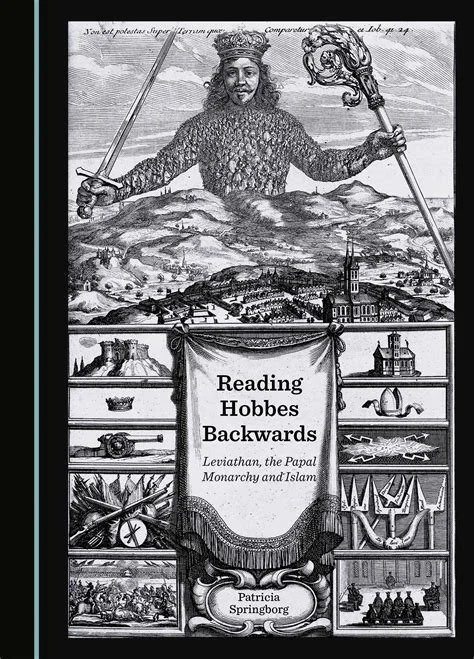

Dr. Springborg also suggests that the ceremonial, representational functions of the Holy Roman Emperor’s served as a kind of model for Hobbes. Borrowing from the work of Dr. Stollberg-Rilinger she argues that the visual and ceremonial strategies of the Emperors may have influenced Hobbes’s account of sovereigns as fictive, representative persons. This is an intriguing suggestion, supported mostly by paralleling Hobbes’s famous frontispiece in Leviathan with engravings depicting the Emperor sitting in majesty amongst his subordinate princes and administrators. (It is unclear what other sources Hobbes would have had on the “culture of presence” that served to elevate the authority of Emperors in these centuries.) This is interesting suggestion, but it induces some hesitation. Dr. Springborg herself notes the presence of papal insignia in the German images, uncongenial to Hobbes of course and – if the images influenced him – duly expunged. One might further wonder if an Emperor portrayed amidst subordinate princes and electors, which suggests perhaps a coordination of estates and corporate powers, quite captures the more extreme version of absolute representation and attributed action symbolized by Leviathan’s body made of anonymous, faceless bodies.

Perhaps the most promising effort to find a Hobbesian interest in the Holy Roman Empire is by way of Bodin, who was undoubtedly an influence on Hobbes and also an important theorist of sovereignty within the Holy Roman Empire. This, in a sense, is the conjunction promised by the chapter’s title and organization. Dr. Springborg has given us some rich, if at times ambiguous, analysis of the likely influence of Bodin over Hobbes. This influence has been understudied for lack of sources, and it is good to have it given attention. Hobbes presumably agreed with Bodin that sovereignty in the Empire necessarily attached to the Imperial Diet which passed all legislation and ratified the treaties that ended the 30 Years War. The monarchical form of sovereignty seemed an untenable theory in the Imperial case if sovereignty, for Bodin and Hobbes alike, was necessarily undivided. But here, Bodin’s influence over Hobbes would seem to have rendered the constitution of the Holy Roman Empire unattractive to him. And Bodin’s influence would seem to draw us to a French context for Hobbes’s thought. That Bodin might have shaped Hobbes’s understanding of the Empire is interesting, but the evidence for the point is quite limited and the implications of such an influence – over, for example, Hobbes understanding of the sovereignty of the Emperor – is ambiguous.

Chapter six closes with some topics only somewhat tangentially related to the subject of Bodin or the Holy Roman Empire: Hobbes’s account of good and evil and his theory of obligation. It might have been useful to consider these subjects in a comparative context. Recent scholarship on Bodin has tended to recover his less absolutist face, his often overlooked deference to preexisting laws and political customs. Bodin certainly did not attach himself to the sort of profound moral conventionalism that Hobbes espoused. The latter portions of this chapter, while not directly about Bodin, might have been usefully put into a comparative frame in order to demonstrate the greater radicalism of Hobbes’s full philosophy when juxtaposed against that of Bodin on subjects such as morality and political obligation.

To sum up my reaction to this interesting chapter, I do not doubt that Bodin was an important source for Hobbes on the nature of sovereignty in the Holy Roman Empire. But I do wonder if the context of the Empire and its history is the most promising prism through which to consider Bodin’s broader influence over Hobbes.

Jeffrey Collins

Professor of Humanities

Hamilton School for Classical and Civic Education

University of Florida