Reading Hobbes Backwards (5)

II. Response: ‘Hobbes the Peace Theorist; Hobbes’s Verse Vita as confessional testimony’, by Patricia Springborg

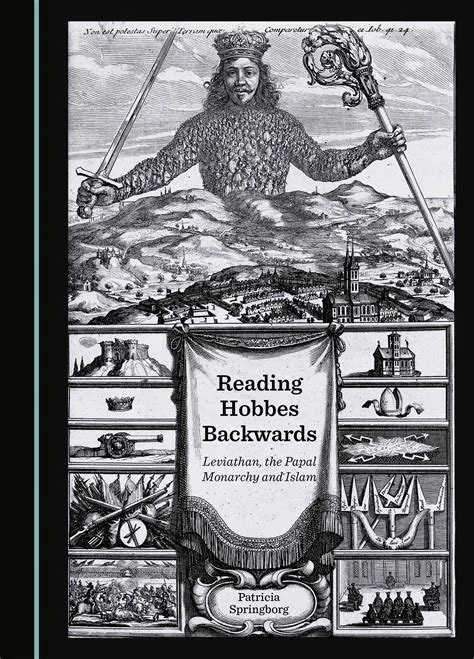

My book, Reading Hobbes Backwards, Leviathan, the Papal Monarchy and Islam (Springborg 2024) addresses Leviathan in the context of an accommodation between ancient classical Greek and Roman civilization, Christianity and Islam that lasted over two millennia. It has been a dilemma for me to know how to introduce such a large project to participants in the Online Symposium being conducted by the European Hobbes Society network; and I sincerely thank the organizers Gonzalo Bustamente, Luka Ribarevic, Luc Foisneau, and the generous participants, Delphine Thivet, Jeffrey Collins and Elad Carmel for their patience. I could not have asked for a more thoughtful and intelligent exposition of my attempt in Reading Hobbes Backwards to show how, under the repressive Jacobean regime, Hobbes the peace-theorist must resort to strategies of ‘surrogacy’, satire and burlesque to protect himself as the purveyor of ‘precarious knowledge’, than Delphine Thivet’s exquisite exposition – better than I could hope to do myself is such a compressed scope! I thank Delphine sincerely, a peace-theorist in her own right, whose early work on Hobbes and peace theory, I found inspiring, but sadly did not include in my bibliography, forgive me Delphine! I no longer have no research assistants and sometimes my lapses of memory are egregious! 1 I can only address it – as I can only address the very intelligent and elegantly expressed queries of my on-line commentators Jeffrey Collins and Elad Carmel – in a sequel to Reading Hobbes Backwards, to which I am already giving thought. There I would undertake a careful reading of relevant sections of Leviathan, to assess the unique claims Hobbes makes for his text in understanding the critical historical moment in the cycle of empires at which it was written. This historical moment accounts not only for the aspirations to empire of newly self-confident Great Britain and Holland as rising maritime powers; but also their colonial ambitions; and, in the case of Britain, the role of the great royally chartered companies, the ‘Virginia and Sommer-islands’ companies, in promoting capitalist-sponsored imperialism. But to explore ‘the ungodly trinity of colonialism, capitalism and slavery’, as I have termed it, is for another day – here I can only anticipate it.

My contribution to this symposium must necessarily be a limited one. Much turns on whether I can redeem my claim to verify Hobbes’s account of the internal constraints placed upon him by the powerful patronage system in which as a client he was situated – a prosopographical exercise concerning asymmetrical systems and the distributions of power they presuppose. It seems to me that the most efficacious way I can respond to the excellent on-line contributions to this symposium of Thivet, Collins and Carmel then, is to examine Hobbes’s late Latin verse Vita, little-read, but for which we have reliable Latin and English versions. Written in the confessional epistolary style Hobbes typically used to claim intellectual property in his commissioned works, the Vita was designed as independent testimony for his intention to produce in Leviathan, a non-commissioned work of philosophy that, he declares, ‘tis hoped by me ... will last to all eternity’, as ‘the rule of justice and severe/ Reproof of those men that ambitious are./’ (‘Hobbes’s Verse Autobiography’, in Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, liv-lxiv, at lx, lines 271-274). Leviathan is a work of acuity that no other political treatise of the period matches, and became a secret bible for Locke; not because Hobbes could claim more or less exclusive ownership of the political theory it espoused; which in fact he could not; but because that theory has never before or since been so powerfully articulated. It was for his theoretical fluency and persuasiveness that the powerful Cavendish family, on the advice of his Oxford rector, employed him. This Hobbes advises us in his Vita, where he refers to ‘Ca’ndish, known to be/ A noble and conspicuous family’/ (Curley Vita, liv-lxiv, at lv, lines 67-8), acknowledging the Cavendish family as being of interest because it was already positioned to benefit from the foundation of the royally patented trading companies, the Virginia and Sommer’s Isles Companies, designed to profit from the colonization of the Americas.

Hobbes’s Latin verse Autobiography, or Vita has a complicated history, for which I rely on the excellent account by Julie E. Cooper 2007.2 Written in 1672 when he was already aged 84, as Hobbes acknowledges in the closing lines of the poem, we have it in both Latin and English. The Latin version was published posthumously as the unauthorized Tomae Hobbesii Malmesburiensis vita authore seipso, or Life of Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury written by himself (London 1679). The following year an anonymous English translation, The Life of Mr Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury (London: Printed for A.C., 1680), was published by Andrew Crooke, to whom Hobbes had entrusted his extant MSs, and sold in Fleet street near Temple Bar. It is the basis for Curley’s version (with updated spelling) that I use here. But in 1681and 1682 Richard Blackburne had included a version of the Latin verse Vita in a volume Thomae Hobbes angli Malmesburiensis philosophi vita, along with 2 additional biographies, a Latin prose biography attributed to Hobbes; and a Latin biography authored by Blackburne, which was largely a translation from Aubrey’s Brief Lives. Blackburne admits to altering the Latin Vita to correct misprints, grammatical mistakes and metrical problems, but he also takes editorial license. It is the text of Blackburne’s Vita that William Molesworth reproduces in his Latin works (OL I: lxxxv-xcix). Meanwhile Edwin Curley, in Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, liv-lxiv), at lxiv, note 68, reports Aubrey recording that the 1680 English translation, appears not to have been made from the printed edition but from a Hobbes MS, and ‘may be a more accurate record of what Hobbes wrote than the Latin’. Julie E. Cooper since reports Quentin Skinner confirming, in a personal communication of 2002, that the unauthorized 1679 Latin edition was in fact typeset from a MS of the Vita in James Wheldon’s hand with corrections by Hobbes – a MS that still exists (Chatsworth: Hobbes MS A.6: untitled). This means that the Latin version is equally duty-worthy. To conclude then, we have in fact reliable editions of both Latin and English versions of Hobbes’s verse Vita, which are worthy of serious attention.

Let me say that Julie E. Cooper’s focus on the Vita in her ‘Thomas Hobbes on the Political Theorist’s Vocation’ (2007), differs greatly from mine. For me the Vita is invaluable as a further instalment in the series of epistolary confessions we acknowledge as Hobbes’s attempts to claim intellectual property in his philosophy, as set out in early works commissioned by the baronial Cavendish family (which I detail in my book); and as set out in the non-commissioned Leviathan. The Vita is especially valuable for: 1) the light it sheds on Hobbes’s role in the Cavendish patronage system; 2) for Hobbes’s account of his recruitment, with the help of his Oxford rector, to a famous family, already positioning itself to profit from empire in the great trading companies founded for the colonization of the Americas; 3) for Leviathan as informed by Hobbes’s own administrative service in the Virginia and Bermuda companies; 4) as a demonstration of how his early commissioned works differ from Leviathan, a work demonstrably non-commissioned; 5) how as a work of Realpolitik, Leviathan, on the basis of prosopography and systems theory, undertakes a trenchant critique of Jacobean clientelism; and 6) how patronage, as productive of statesmen and place-men, who, through the inversion of accepted ‘ethical values’, produced a system of richly-rewarded politicians, rather parasitic on the court than devoted to its service. 7) It was written in Latin, thus establishing Hobbes’s credentials as a practitioner of civic humanism, to which knowledge of ancient Greek and Latin were critical; and as the teacher hired by the baronial Cavendishes, determined to leave a lasting legacy. 8) But writing his Vitas, like his Historia Ecclesiastica, in Latin was also a further exercise in political surrogacy, offering Hobbes some protection from the ‘hoi polloi’, who did not read this, the language of literacy in which the coin of clientage was cashed.

Hobbes’s intention to defend his philosophical life as unified and purposeful, devoted to service and science, is immediately evident in the Vita. He tells us how, even as an Oxford student studying the obligatory Aristotelian physics, he had developed an interest in the science of navigation and its possibilities: ‘My fancy and my mind divert I do,/ With maps celestial and terrestrial too/..... How Drake and Cavendish a girdle made/ Quite round the world, what climates they survey’d/’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lv, lines 56-60). Then, having completed his ‘first degree/, Of Bachelor i’th’ University/ Then Oxford left, serv’d Ca’ndish, known to be/ A noble and conspicuous family./’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lv, lines 65-68). He is quite open about how the patronage system worked; that he owed his appointment to an Oxford recommendation; that he was hired to tutor the 2nd Earl of Devonshire (1590—1628), not much younger than himself; and that they enjoyed not only patron/client relations but close friendship for 20 years: ‘Our college rector did me recommend,/ Where I most pleasantly my days did spend./Thus youth tutor’d a youth, for he was still/ Under command and at his father’s will:/ Serv’d him full twenty years, who proved to be,/ Not a lord only, but a friend to me’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lv, lines 67-74). We learn that Cavendish supplied books to the Hardwick Hall library – for which we still have Hobbes’s own 1630s booklist (Chatsworth MS E1A): ‘Thus I at ease did live, of books, whilst he/ Did with all sorts supply my library/’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lv, lines 77-78).

Hobbes does not neglect to detail the civic humanist education for which he had been hired as a tutor, including his translation of Thucydides, in 1629, his first official publication: ‘Then I our own historians did peruse,/ Greek, Latin and convers’d too with my muse./ Homer and Virgil, Horace, Sophocles,/ Plautus, Euripides, Aristophanes,/ I understood, nay more, but of all these,/ There’s none that pleas’d me like Thucydides./ He says Democracy’s a foolish thing, / Than a republic wiser is one king,/ This author I taught English, that even he/ A guide to rhetoricians might be./’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lv-lvi, lines 79-88). Hobbes is establishing his credentials as a royalist – a position that he might have reluctantly relinquished under Cromwell, but to which he returned in the Restoration. He is also specific that a civic humanist education, with fluency in Latin, the language of literacy, was designed to deliver his student from the rhetoricians – the ancient Platonist and Aristotelian defence of philosophy. It also belonged to the humanist curriculum to make the ‘grand tour’ of classical European cultural sites, which he did, travelling in the retinue of his pupil, the 2nd earl of Devonshire: ‘To foreign countries at that time did I/ Travel, saw France, Italy, Germany,/ This debonair lord, th’Earl of Devonshire,/ I served complete the space of twenty year/’. Hobbes then goes on to tell us that with the early death of his pupil, he regretfully left the Cavendish household and went to Paris: ‘I left my pleasant mansion, went away/ To Paris, and there eighteen months did stay,/’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lv-lvi, lines 89-98).

During the break in Cavendish patronage due to the early death of his pupil, Hobbes was briefly secretary to Sir Gervaise Clifton (1587-1666) , an MP for successive north country electorates, and a Royalist in the English Civil War. But in 1631 Hobbes was called back into Cavendish service for a period of 7 years to tutor the 3rd Earl of Devonshire: ‘Thence to be tutor I’m cal’d back again,/ To my Lord’s son, the Earl of Devon then./ This noble lord I did instruct when young,/ Both how to speak and write the Roman tongue;/ And by what arts the rhetor deceives those/ That are illiterate; taught him verse and prose;/ The mathematic precepts too, with all/ The windings in the globe terrestrial;/ The whole design of law, and how he must/ Judge between that which equal is and just./ Seven years to him these arts I did explain/’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lvi, lines 99-109).

Again Hobbes’s duties included a ‘grand tour’, this time to Italy and France in the entourage of his new pupil (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lvi-lvii, lines 113-128). During this time Hobbes admits to having ‘scribbled nothing’ (Vita, line 129). After his 2nd period of Cavendish service Hobbes returned to Paris; where he enjoyed the hospitality of the Cavendish French network: ‘Here with Mersennus I acquainted grew, / Shew’d him of motion what I ever knew./ He both prais’d and approv’d it, and so, Sir,/ I was reputed a philosopher.’/ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lvii, lines 133-136). Over a period of 8 months, Hobbes tells us (Vita, line 137), he formulated his tri-partite philosophy concerning: matter in motion ‘and the different Species of Things’ (De Corpore, Vita, lines 141-142); ‘Man’s Inward Motions and his Thoughts’ (De Homine, Vita, line 143); ‘The good of Government and Justice too’ (De Cive, Vita, line 144). Hobbes declares this tri-partite philosophy, comprising 3 books, constituted his ‘whole Course of Philosophy’ then – and by implication, still, at the time the Vita was being written – ‘These were my Studies then, and in these three/ Consists the whole Course of Philosophy./Man, Body, Citizen, for these I do/ Heap Matter up, designing three Books too.’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lvii, lines 145-148). But publication of his philosophy in its correct sequence faced obstacles.

Civil war intervened, and in 1640 an episode of the Plague: ‘Two years elaps’d, I published in Print/ My Book De Cive; the new Matter in’t/ Gratified Learned Men, which was the Cause,/ It was Translated, and with great Applause/ By Several Nations, and great Scholars read,/ So that my name was Famous, and far spread./’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lvii-lviii, lines 159-164). Hobbes reports his efforts ‘To Pen my Book De Corpore, Night and Day’ (Vita, line 170). A lengthy paeon to Mersenne follows: ‘Learned, Wise, Good, whose single Cell might be/ Prefer’d before an University./’ (Vita, lines 177-178). Hobbes next tells of the English Civil War and the flight of Charles, the Prince of Wales, to Paris, which caused him to again be called upon as tutor: ‘My Prince’s studies I then waited on,/ But could not constantly attend my own./’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lviii, lines 170-204). Having recovered from a serious illness, Hobbes records how he finished his work, ‘in my own Mother-Tongue,/ To be read for the good of old and young,/ The Book at London printed was, and thence,/ Hath visited the Neighbouring Nations since, / Was read by many a great and learned Man, /Known by its dreadful name, Leviathan, /This book contended with all kings, and they/ By any title, who bear royal sway./’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lix, lines 206-214). Hobbes’s pride in the international impact of Leviathan, enhancing his reputation as a philosopher, is noteworthy, supporting my view that Hobbes saw himself primarily as a European peace-theorist; but equally noteworthy is his insistence that this work was purposively written in English, and not Latin, to address specifically his royalist patrons, and his pupil the King.

Hobbes’s Latin verse Vita, written so long after the events it describes, does not present the view that Leviathan was an attempted accommodation with Cromwell and his Independents. But it does not succeed in dismissing it, either. Reporting how ‘In the mean time the King’s sold by the Scot,/ Murder’d by th’English, an eternal blot./’, while ‘King Charles at Paris who did then reside,/ Had right to England’s Scepter undenied/,’ Hobbes proceeds to give an extremely unflattering account of Cromwell and the Independents: ‘A rebel rout the kingdom kept in awe,/ And ruled the giddy rabble without law,/ Who boldly Parliament themselves did call,/ Though but a poor handful of men in all./ Blood-thirsty leeches, hating all that’s good,/ Glutted with innocent and noble blood.’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lix, lines 215-224). Our suspicions might well be raised by his extravagant language; and especially when Hobbes gilds the lily on the episcopacy, to whom we know he was opposed: ‘Down go the miters, nor do we see/ That they establish the Presbytery./ Th’ambition of the stateliest clergymen,/ Did not at all prevail in England then./’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lix, lines 225-228). Those ‘stately clergymen’, the bishops, turned out in fact to be Hobbes’s most vocal enemies.

Hobbes tells of delayed reaction to the boldness of Leviathan, so that two years after its publication, during which his studies were undisturbed, suddenly, ‘When that book was perused by knowing men, / The gates of Janus temple opened them;/ And they accused me to the King, that I/ seemed to approve Cromwell’s impiety,/ And countenance the worst of wickedness:/ This was believed, and I appeared no less/ Than a grand enemy, so that I was for’t/ Banished both the King’s presence and his court./’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lix, lines 233-239). Hobbes confesses in despair to ruminating on the fate of Dorislaus (1595-1649), the Dutch Calvinist in English service, appointed an ambassador by parliament, but assassinated by Royalists to avenge the death of Charles I; and of Roger Ascham (1515-1568), the Cambridge-educated humanist, scholar, Greek and Latin tutor to Elizabeth I, who died early, leaving his children in penury (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lix, lines 241-242). At this point Hobbes admits to tremendous fear at his prospects: ‘And stood amazed, like a poor exile, /Encompassed with terror all the while./ Nor could I blame the young King for his Assent/ To those intrusted with his government./’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lix-lx, lines 243-246). Hobbes confesses in desperation to going ‘home’ to England: ‘Then home I came, not sure of safety there, /Though I could not be safer anywhere./’, admitting that: ‘At London, lest I should appear a spy,/ Unto the state myself I did apply;/’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lx, lines 247-248, and lines 251-252). Apparently intent on exonerating himself, Hobbes asks, ‘What royalist can there, or man alive, /Blame my defense o’the’King’s prerogative?/ All men did scribble what they would, content/ And yielding to the present government./’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lx, lines 259-262). But not Hobbes, is the implication – or is it? Carefully read, Leviathan demands of royalists that under Cromwell they rethink their political loyalty.

Hobbes reports his studies continued unhindered; that after two years De corpore was published; and that he held high hopes, despite public condemnation, that both his philosophical and scientific works, Leviathan and De corpore, would stand as his legacy for all time: ‘The clergy at Leviathan repines,/ And both of them opposed were by divines./ For whilst I did inveigh ‘gainst papal pride, / These, though prohibited, were not denied/ T’appear in print: gainst my Leviathan/ They rail, which made it read by many a man,/ And did confirm’t the more; tis hoped by me,/ That it will last to all eternity./’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lx, lines 265-272). Of Leviathan, he claims with final satisfaction: ‘T’will be the rule of justice and severe/ Reproof of those men that ambitious are./ The King’s defence and guard, the people’s good,/ And satisfaction, read, and understood./’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lx, lines 273-276).

Hobbes goes on to defend De corpore at length, as an exercise not only in mathematically based science, but also in ethics: ‘I, two years after, print a book to show/ How every reader may himself well know./ Where I teach ethics, the phantoms of the sense,/ How th’wife with spectres, fearless may dispense./ Published my book de corpore withal,/ Whose matter’s wholly geometrical./ With great applause the algebrists then read/ Wallis his algebra now published.’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lx, lines 277-284). These lines preface a predictably long rant against John Wallis (1616 – 1703), English clergyman and mathematician – who indeed had a great deal more talent than Hobbes allows. Wallis is today credited with assisting the development of infinitesimal calculus, to which Isaac Newton (1643 – 1727) and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646—1716), also later contributed. But Hobbes rants on dropping some very significant names: ‘A hundred years that geometric pest/ Ago began, which did that age infest./ The art of finding out the numbers sought/ Which Diophantus once, and Gheber taught:/ And then Vieta tells you this,/ Each geometric problem solved is./’ (Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, lx-lxi, lines 284- 290).

Hobbes is showing off – not only his knowledge of the Arabic transmission of ancient Greek mathematics; but also his French mathematical erudition. For, Diophantus of Alexandria (fl. 250 CE), a Greek, was the author of Arithmetica in 13 books, of which 6 are extant in Greek, and 4 have been recently discovered in Arabic; the oldest extant work to solve arithmetical problems using algebra.3 Moreover, the 1621 edition of Arithmetica produced by the Frenchman Claude Gaspar Bachet (1581-1636), was made famous by Pierre de Fermat (1601-1665), who wrote his famous ‘Last Theorem’ in the margins of his copy. Geber, however, is the Latinized form of the Arabic name Jabir, and could refer to several mathematicians: Jabir ibn Hayyan (died c. 806-816 CE), an early Islamic alchemist and polymath; or the anonymous 13th and 14th century Latin writings attributed to ibn Hayyan, but referred to as Pseudo-Geber. Geber could also refer to Jabir ibn Aflah (1100-1150 CE), the Spanish-Arab astronomer and mathematician. While Vieta is a reference to ‘Vieta’s formulas’, which solve the problem of relating the coefficients of a polynormal to the sums and products of its roots, without having to compute them individually. Named for Francois Viete (1540-1603), who was known as Franciscus Vieta – it was also a case of name-dropping by Hobbes, the notorious name-dropper, who seemed to believe that his scientific credentials depended on conspicuous display.

It is fitting to close this online symposium with a reaffirmation of Hobbes’s knowledge of the transmission of ancient Greek mathematics through Islam, to the great mathematicians of his own day. For, his late Latin verse Vita, intended as independent verification of Hobbes’s intentions in both his commissioned and non-commissioned works, is the last example we have of his rather obsessive behaviour, where, working under the constraints of patronage and a repressive regime, from the moment we first encounter him, he is forced to insert his work in progress opportunistically ‘into whatever high-profile vehicles came to hand, favouring epistles dedicatory and other high profile genres until, with Leviathan, he could have his works printed in his own persona' (Springborg 2024, Preface, p. xii). Delphine Thivet has given an excellent account of my attempt to show how Hobbes’s special combination of scribal publications and serial texts, involving satire and surrogacy, worked. I can only hope that my concluding exposition of his little-read, but eminently duty-worthy late Latin Vita, for which we also have a reliable English translation, serves as proof that we should look carefully at what Hobbes has to say about his project for peace and justice, which he hoped (Hobbes’s verse Vita, in Lev., Curley 1994 edn, Vita, liv-lxiv, at lx, lines 271-274) would ‘last to all eternity’, as ‘the rule of justice’ and ‘severe Reproof’ to ambitious men. To an extraordinary degree Hobbes’s wish has been fulfilled, now celebrated as the first and greatest encyclopaedic philosopher to write in English. And for his courage to speak truth to power in Leviathan, by insisting that under the terms of the ‘Engagement’ with Cromwell, Royalists, and even the King, must reexamine their political obligations, we can only commend him for his bravery. It is also worth noting, however that he did make a couple of attempts to test the water before doing so – first in De cive, intended for the court in exile in Paris and the Cavendish European network centred there; and second in the English translation of De Cive, published in London in a purportedly unauthorized edition (but probably semi-authorized) in March 1651, only months in advance of Leviathan, and entitled: Philosophical Rudiments Concerning Government and Society, where, as in the letter dedicatory to his patron prefacing De Cive, he openly seeks approval and approbation of his method, inviting commentary and criticism – here the cautious Hobbes, testing the waters. But these are also discussions for another day.

1 See Delphine Thivet 2008, ‘Thomas Hobbes: a philosopher or war or peace?’, British Journal for the History of Philosophy 16 (4):701-721, who treats Hobbes as a peace theorist, calling into question the moral scepticism of the ‘realist’ school of Hobbes interpretation.

2 Julie E. Cooper, ‘Thomas Hobbes on the Political Theorist’s Vocation’, The Historical Journal, 50, 2 (2007): 519-547, note 67 at pp. 534-535. (DOI: https;//doi.org/10.1017/50018246X007006243.)

3 The literature on the history of mathematics is of course vast, but see Jean Christianidis and Jeffrey Oakes, 2013: ‘Practicing algebra in late antiquity: the problem-solving of Diophantus of Alexandria’, Historia Mathematica 40 (2): 158-160.